The chaos of a crisis can affect any private or public organization, impacting an array of stakeholders, those the crisis affects, and from whom the organization requires support. In broad terms, a crisis is any unexpected incident potentially upsetting an organization’s employees, customers, operations, reputation, finances, or the local, national, or international community.

Any organization can encounter an emergency at any time, which requires effective communication during and after the incident. Crises, such as workplace or school violence, transport accidents, terrorist attacks, or corporate scandals, differ in cause, severity, and consequence. Crises, however, share specific characteristics:

- Confusion surrounds the scene but slowly evolves into some degree of order.

- The on-scene response is critical as it contributes to the chain reaction of events and media coverage of the organization’s capabilities.

- Events escalate as challenges confront the response team, possibly attracting media speculation.

- Information is initially conflicting and tends to arrive in sudden bursts.

- Public interest soars initially, especially for reassurance, and then tends to diminish.

- External influence is unavoidable as reporters, politicians, competitors, commentators, regulators, and others, many of whom know little about the organization(s) involved, comment on the response and impact the overall message. This, in turn, influences public perception of the response effort.

1.2 Role of Crisis Communications

Communication is critical in facilitating public and private organizations’ crisis response efforts. It is in an organization’s interest to have a crisis communications plan to release verified information quickly. In doing so, it must express its empathy for any losses, its ability to resolve the crisis, and its dedication to mitigate further damages.

In a perfect world, one spokesperson would serve as the sole source of information on an incident. However, organizations in a crisis face the challenge of managing information while other channels can provide unanticipated and/or critical information affecting response operations.

“Media and online coverage significantly influence operational outcomes and public expectations.”.

Therefore, organizations must form a flexible and quickly activated Crisis Communications Team (CCT) to implement a communications plan as a part of their response effort.

Otherwise, the media and online communities will meet their deadlines with or without the organization’s input. By its very nature, the media dislikes an information vacuum. It must be filled, if not by the organization, then by uninformed outsiders. Also, other involved entities will not conduct public relations on behalf of our client organization.

The Crisis Communications Manual provides planning, response, and post-incident procedures for organizations to communicate with their stakeholders and the media to inform, calm, and direct the public during crises.

1.3 Consequences of Inadequate Communications

When an emergency occurs, crisis response teams (both government and private) tend to focus on mitigating the immediate effects of the incident.

Communication with stakeholders and the media is generally an afterthought. Any organization without a practiced response and communications plan will inevitably fail to coordinate messages among staff, partners/authorities, stakeholders, and the public via the media and online platforms.

Also, reporters covering ‘breaking news’ often arrive on-site before, or soon after, the communications and/or – response team. Without a quick response to the media, early press coverage, which often sets the tone for subsequent coverage, may be inaccurate or incomplete.

Preparation on all levels is vital for an effective communications response. For instance, if a receptionist fails to locate a spokesperson for a press inquiry, he or she could be responsible for a line in the story stating, “A company spokesperson could not be reached for comment,” suggesting secretiveness on the part of the organization.

The Oxford University study ‘The Impact of Catastrophes on Shareholder Value, concluded that corporations lost an average of 5 percent in net stock value in the months following an ineffective response to a large-scale emergency.

Message failures can lead to fatalities, casualties, lost elections, decreased funding, litigation, forfeited public/customer trust, and/or property damage, which could otherwise be prevented with a regularly rehearsed and updated crisis communications plan.

1.4 Benefits of Effective Crisis Communications

A well-executed crisis communications response effort will increase an organization’s credibility by:

- Providing vital information to stakeholders

- Displaying the organization’s authority and capabilities

- Maintaining the organization’s operations and mitigating losses

- Using the press cycle to aid response and recovery management

The Oxford University study found that companies that managed a successful recovery gained an average of 5 percent in net stock value over the same period as the ineffective corporations lost value. An effective response also increased companies’ total market value by approximately 22 percent. The study asserts, “Although all catastrophes have an initial negative impact on [company] value, paradoxically, they offer an opportunity for management to demonstrate their talent in dealing with difficult circumstances.” Furthermore, in the public eye, the positive impact of credible crisis response outweighs proof of financial well-being or recourse to those affected.

1.5 Changing security environment

The Al-Qaeda terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, brought into sharp focus the need for organizations to prepare for widespread and sustained media attention. With little preparation, public and private CCT members and the media had to work closely together to disseminate calming and accurate information to the public.

The multi-layer response efforts included:

- Rescue and recovery missions in New York, Washington, DC and Pennsylvania

- New levels of security imposed in the United States

- Emergency closures and their impact on the US stock market, trade, and travel flows, as well as the reverberations through the international economy

- Broadened international collaboration on counter-terror protection

- Cooperative international investigation of the attacks

- An international military campaign in Afghanistan

While these issues were still being assessed and addressed, the October 2001 anthrax threat to the US Postal Service, Congress, and the media itself exacerbated the uncertainty and increased the media’s response to any security-related news.

Media attention to these incidents also revealed response difficulties partly due to poor internal and external communication plans. For example, the US government did not have a unified internal broadcast system to evacuate government employees vulnerable to the terrorist attacks in the Washington, DC metropolitan area. The New York Police Department required several days to implement a cohesive communications action plan.

A CNN National Correspondent reported:

“I arrived in New York City around 3:00 in the morning, about 18 hours after the first plane struck the tower. Media access completely depended on which police officer you approached. If there was one message, it wasn’t being communicated. Some officers would not let us drive on certain streets or go past barricades. Yet, we often found other officers who would. It is an uncomfortable position to have to shop for media-friendly officers, but the lack of organization and public need for information forced us to do so. As the days went by, the situation became very organized.

For the most part, however, police did not allow the news media access to the Ground Zero site. Critical work was still taking place on the site, but allowing reporters access to such a huge area would not have hampered that work or caused any security problems. It also would have allowed our viewing public to have more information in those initial confusing and frightening days.”

Although the scale of attacks on New York was beyond any pre-incident plans, our after-action review reveals some causes of a breakdown in orderly coverage, adversely affecting the organization’s message to the public:

- Failure to deliver a unified message and perimeter rules causes the media to go outside of the official CCT for site access and information.

- Employees on-site act outside of the organization’s command structure by independently serving as spokespersons in some capacity and managing perimeters/site access

Conversely, then Commander of the US National Guard Weapons of Mass Destruction Civil Response Unit in New York reported the cooperation he experienced with the media on September 11:

“The media was on hand in force and knew the Civil Support Team was tied up in several sensitive operations. The media wanted interviews and information on operations. Because we had trained with the media on hand prior to the incident and conducted interviews in the past, they knew our mission and the sensitivity of its nature. They worked out a time and place for interviews by holding meetings with the different sections. The media played a vastly different role by gathering this information and disseminating it back for the other sections to use in their operations. The media acted as a conduit and assistor in the information flow.

Lesson learned: train with the media to ensure they know about your mission. Help them, [and] they will help you.

These examples show that, ultimately, both the organizations involved in a crisis and the media can, and in most cases want, to work together to inform the public.

Another impact of September 11 on the media and security environment is that an incident occurring in one location can have a major impact elsewhere.

For instance, a terrorist attack on a ship in a port in Yemen will bring scrutiny to organizations responsible for port security elsewhere around the world.

The new security environment makes it imperative to create, update, and practice crisis communications plans with all employees before incidents occur.

This planning will allow organizations to interact with media to calm the public while balancing the demands of operations and safety precautions.

1.6 Faster media cycle in response to crises

Two major dynamics have increased media response time to incidents. First, the current security environment demonstrates how the media can serve as a critical infrastructure and even ‘first responder’ to disseminate public safety information. Second, advances in information-based technology have significantly shortened media response time and increased access to different sources of information.

The continuing threat of multi-layer, safety-related crises has heightened press interest and public desire for calming yet accurate messages. Consequently, the media currently tend to infer that a security incident may be terrorism-related until it can be disproved.

For instance, when a suspected chemical-biological threat at Miami International Airport occurred, within five minutes of the response dispatch, the local, national, and international media sent inquiries to the Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Public Affairs Office. Ultimately, the incident’s cause was not terrorism as speculated or even serious. (See Chapter 3: Planning Procedures for the full case study).

While the media usually react quickly to any news related to possible security threats, their limited resources and desire to report exclusives also shift their attention more quickly to the next big incident. In other words, the media targets more resources for a particular story but for a shorter amount of time. For example, the TWA Flight 800 crash off the coast of New York in 1996 caused 230 fatalities and attracted over 600 members of the press for over 30 days. In contrast, the media coverage of the American Airlines Flight 587 crash in Queens, New York, on November 12, 2001 – which had more casualties, a similar potential terrorist cause, and proximity to the same large media market – lasted for only about three days. In 2024, the tendency is to focus on a specific incident only until another incident demands attention. Often, incidents that would have lasted days in the past now only get a mention on broadcast news or are allotted to online news sites only.

The expansion of the Internet, cable television, and wireless communications facilitates quicker information access and delivery, creating a new media environment. For example, online searches provide a myriad of background information revealing organizations’ past mistakes. This means that spokespersons must be informed and prepared for probing questions. With this abundance of information, the media presents stories in a more condensed form and, therefore, seeks striking quotes for 10- to 12-second sound bites. Some media organizations also combine elements of straight reporting and entertainment, whereby reporters may use controversy and sensationalism to increase ratings and, thereby, advertising revenue.

The security environment and competitive pressures of the media industry heighten the need for organizations to form and test crisis response plans with a solid communications component.

1.7 Crisis cycle phases: response, communications, and media

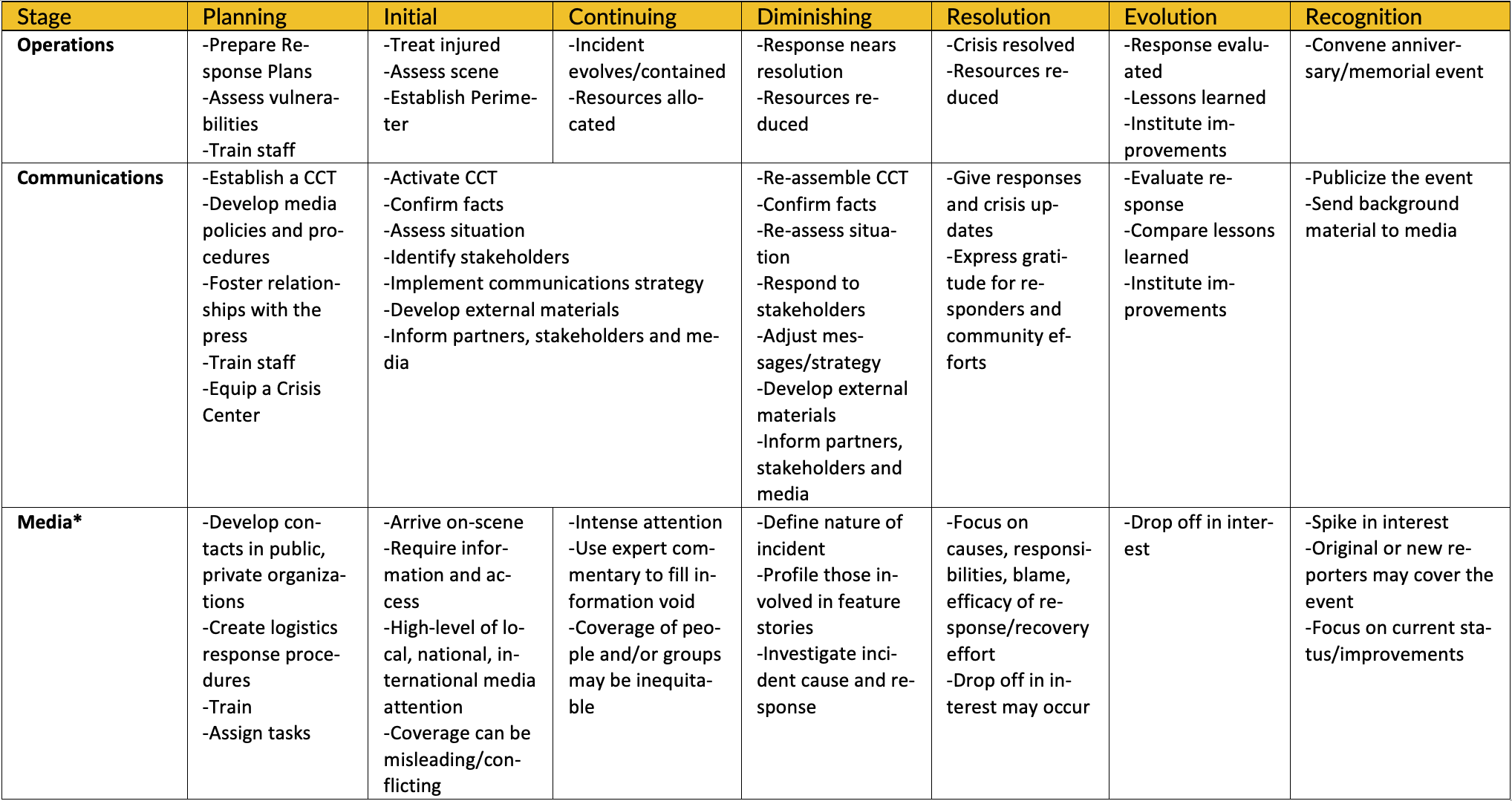

Most crises typically follow a similar sequence or structure. Both short- and long-term crisis response operations require a communications plan to be implemented simultaneously with other elements of the response. The media, in turn, responds to these phases, requiring the CCT to inform them of developments. The following table details the phases of crises, communications, and media response cycles and illustrates how they work in parallel.

Crisis cycle phases: response, communications and media

1.8 Incident-based crisis communications

While every crisis communications response must execute the action plan, this handbook

discusses a wide range of potential crises that attract varied types of media attention and require different internal and external communications responses.

- Natural disasters: sudden events, such as earthquakes, tornadoes, disease outbreaks or slower-moving events such as hurricanes and monsoons

- Human-caused hazards: unexpected, sometimes inexplicable human phenomena, such as (bio) terrorism, hoaxes, school or workplace violence, civil disturbances, and armed conflict

Mechanical/technological malfunctions: failures of public infrastructure or operations, such as transportation accidents, product failures, and workplace facility emergencies.

1.9 Public and private crisis communications

Depending on the level of the crisis, the incident may involve many spokespersons and communications mechanisms across the public and private sectors. Their legal obligations to release information, however, differ.

Most Government agencies have procedures usually guided by freedom of information policies in order to be accountable to the public. The desire for information may come in different forms: media inquiries, formal petitions for documents, letters of inquiry, or phone calls to lawmakers and officials. Public agencies have stipulations on releasing certain types of information affecting operations, security, investigations, and victims and their families. Most public organizations also respond to emergencies using the Incident Command System (ICS) to manage the incident with five functional areas:

- Command (centralized location of management)

- Operations

- Planning/Intelligence

- Logistics

- Finance and administration.

The senior communications officer works in the command structure with the other incident command managers. In this handbook, that officer is referred to as the CCT Leader.

In practice, the title varies from agency to agency. Public agencies should be encouraged to clear all procedures adapted from this handbook with established ICS standard operating procedures.

Private organizations, by contrast, can deem certain information proprietary and protect it from public scrutiny or discovery in legal actions. Private organizations, especially when they have investors, must be more cautious about the information they make public, as this information may affect stock prices, financial standing, or competition. Since private organizations do not have to follow mandated communications policies, they often do not have crisis communications procedures in place and, therefore, greatly increase the risk of adverse consequences of an inadequate response.

When both types of organizations need to respond to the same incident, they must be aware of each other’s information constraints. For example, Joint Information Centers (JIC) – mechanisms for organizations to coordinate and deliver their messages – are under the auspices of one lead organization, most likely a government entity responsible for managing the response operation.

Overall, public safety can depend on the ability of responders, CCTs, and the media to inform, calm, and listen to the public – the most critical infrastructure.

Organizations, therefore, have a responsibility to plan and practice communication procedures to respond efficiently and quickly to emergencies.